WHAT IS COLORECTAL CANCER?

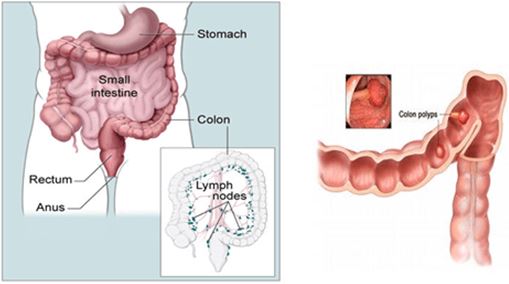

Colorectal cancer is a cancer that starts in the colon (the main part of the large intestine) or the rectum (the passageway connecting the colon to the anus). Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in both men and women.

Most colorectal cancers begin as a growth on the inner lining of the colon or rectum called a polyp. Some types of polyps can change into cancer over the course of several years, but not all polyps become cancer. The chance of changing into a cancer depends on the kind of polyp. The 2 main types of polyps are:

- Adenomatous polyps (adenomas): These polyps sometimes change into cancer. Because of this, adenomas are called a pre-cancerous condition.

- Hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory polyps: These polyps are more common, but in general they are not pre-cancerous.

Dysplasia, another pre-cancerous condition, is an area in a polyp or in the lining of the colon or rectum where the cells look abnormal (but not like true cancer cells).

The wall of the colon and rectum is made up of several layers. Colorectal cancer starts in the innermost layer (the mucosa) and can grow through some or all of the other layers. When cancer cells are in the wall, they can then grow into blood vessels or lymph vessels (tiny channels that carry away waste and fluid). From there, they can travel to nearby lymph nodes or to distant parts of the body.

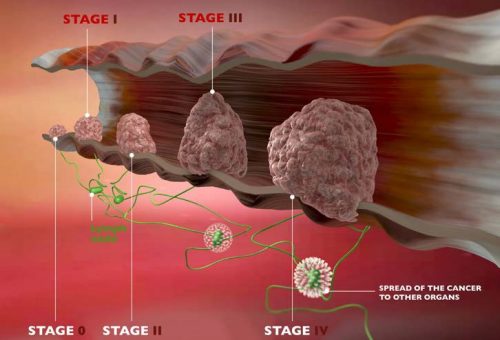

The stage (extent of spread) of a colorectal cancer depends on how deeply it grows into the wall and if it has spread outside the colon or rectum.

WHO IS AT RISK?

Several lifestyle-related factors have been linked to colorectal cancer. In fact, the links between diet, weight, and exercise and colorectal cancer risk are some of the strongest for any type of cancer.

Being overweight or obese: If you are overweight or obese (very overweight), your risk of developing and dying from colorectal cancer is higher. Being overweight raises the risk of colon cancer in both men and women, but the link seems to be stronger in men.

Physical inactivity: If you are not physically active, you have a greater chance of developing colorectal cancer. Being more active might help lower your risk.

Certain types of diets: A diet that is high in red meats (such as beef, pork, lamb, or liver) and processed meats (such as hot dogs and some luncheon meats) can raise your colorectal cancer risk. Cooking meats at very high temperatures (frying, broiling, or grilling) creates chemicals that might raise your cancer risk, but it’s not clear how much this might increase your colorectal cancer risk. Diets high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains have been linked with a lower risk of colorectal cancer, but fibre supplements have not been shown to help.

Smoking: People who have smoked for a long time are more likely than non-smokers to develop and die from colorectal cancer. Smoking is a well-known cause of lung cancer, but it is also linked to other cancers, like colorectal cancer.

Heavy alcohol use: Colorectal cancer has been linked to heavy alcohol use. Limiting alcohol use to no more than 2 drinks a day for men and 1 drink a day for women could have many health benefits, including a lower risk of colorectal cancer.

Being older: Younger adults can develop colorectal cancer, but your chances increase markedly after you turn 50.

Family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps: Most people with colorectal cancer have no family history of colorectal cancer. Still, as many as 1 in 5 people who develop colorectal cancer have other family members who have been affected by this disease

A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease including ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease

Having an inherited syndrome: About 5% to 10% of people who develop colorectal cancer have inherited gene defects (mutations) that can cause family cancer syndromes and lead to them getting the disease. The most common inherited syndromes linked with colorectal cancers are familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, or HNPCC), but other rarer syndromes can also increase colorectal cancer risk.

COLORECTAL CANCER SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Colorectal cancer might not cause symptoms right away, but if it does, it may cause one or more of these symptoms:

- A change in bowel habits, such as diarrhoea, constipation, or narrowing of the stool, that lasts for more than a few days

- A feeling that you need to have a bowel movement that is not relieved by doing so

- Rectal bleeding

- Blood in the stool, which may make it look dark

- Cramping or abdominal (belly) pain

- Weakness and fatigue

- Unintended weight loss

Colorectal cancers can often bleed into the digestive tract. While sometimes the blood can be seen in the stool or make it look darker, often the stool looks normal. But over time, the blood loss can build up and can lead to low red blood cell counts (anaemia). Sometimes the first sign of colorectal cancer is a blood test showing a low red blood cell count.

Most of these problems are more often caused by conditions other than colorectal cancer, such as infection, haemorrhoids, or irritable bowel syndrome. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed

IMPORTANCE OF COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING

Screening is the process of looking for cancer or pre-cancer in people who have no symptoms of the disease. Regular screening can often detect colorectal cancer early, when it is most likely to be curable. In many cases, screening can also prevent colorectal cancer as some polyps or growths can be removed before they have the chance to develop into cancer. There are several tests that examine the colon and rectum and are used to find and diagnose colorectal cancer.

Faecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT): a test to check stool for blood than can only be seen with a microscope. Small samples of stool are placed on special cards and returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing. The FOBT is a quick and convenient screening test to detect early stages of colorectal cancer.

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy: this procedure examines the rectum and the sigmoid (lower) colon for polyps or cancer. A flexible, thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing is inserted through the rectum into the sigmoid colon.

Colonoscopy: this procedure allows examination of the whole colon for polyps or cancer. A colonoscopy (a thin, tube-like instrument) is inserted through the rectum into the colon usually under general anaesthesia.

Virtual colonoscopy, also called CT colonography, is a method of screening the colon for precancerous polyps using a CT scanner. CT colonography provides an interior view of the colon (the large intestine) without a colonoscope and without sedation.

Screening Guidelines

Beginning at age 50, both men and women should follow one of these testing schedules:

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years, or

- Colonoscopy every 10 years, or

- CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) every 5 years

Some people should be screened using a different schedule because of their personal history or family history. Talk with your doctor about your history and what colorectal cancer screening schedule is best for you.

COLORECTAL CANCER STAGES

The stage of a cancer describes the extent of the cancer in the body. The stage is one of the most important factors in deciding how to treat the cancer and determining how successful treatment might be. For colorectal cancer, the stage is based on:

- How far the cancer has grown into the wall of the intestine

- If it has reached nearby structures

- If it has spread to the nearby lymph nodes or to distant organs

The stage of colorectal cancer is based on the results of physical exams, biopsies, and imaging tests (CT or MRI scan, x-rays, PET scan, etc.), as well as the results of surgery.

- If the stage is based on the results of the physical exam, biopsy, and any imaging tests you have had, it is called a clinical stage.

- If you have surgery, the results can be combined with the factors used for the clinical stage to determine the pathologic stage.

Sometimes during surgery the doctor finds more cancer than was seen on imaging tests. This can lead to the pathologic stage being more advanced than the clinical stage.

Most patients with colorectal cancer have surgery, so the pathologic stage is most often used when describing the extent of this cancer. Pathologic staging is likely to be more accurate than clinical staging, as it allows your doctor to get a first-hand impression of the extent of your disease.

The staging system most often used for colorectal cancer is the TNM system. The TNM system is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- How far the main (primary) tumour (T) has grown into the wall of the intestine and whether it has grown into nearby areas.

- If the cancer has spread to nearby (regional) lymph nodes (N). Lymph nodes are small bean-shaped collections of immune system cells to which cancers often spread first.

- If the cancer has spread (metastasised) to other organs of the body (M). Colorectal cancer can spread almost anywhere in the body, but the most common sites of spread are the liver and lungs.

Treatment of colorectal cancer

Treatment for colorectal cancer is based largely on the stage (extent) of the cancer, but other factors can also be important. People with colorectal cancers that have not spread to distant sites usually have surgery as the main or first treatment.

In cancer care, different types of doctors often work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that usually includes or combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. For colorectal cancer, this generally includes a surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, and a gastroenterologist.

Polypectomy

Stage 0 colorectal cancers are these cancers that have not grown beyond the inner lining of the colon or the rectum. For these cancers the usual treatment is a polypectomy, or removal of a polyp, during a colonoscopy. There is no additional surgery unless the polyp cannot be fully removed.

Surgery

Surgery is the removal of the tumour and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. This is the most common kind of treatment for colorectal cancer and is often called surgical resection

- Laparoscopic surgery. Some patients may be able to have laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. With this technique, several viewing scopes are passed into the abdomen while a patient is under anaesthesia. The incisions are smaller and the recovery time is often shorter than with standard colon surgery. Laparoscopic surgery is as effective as conventional colon surgery in removing the cancer.

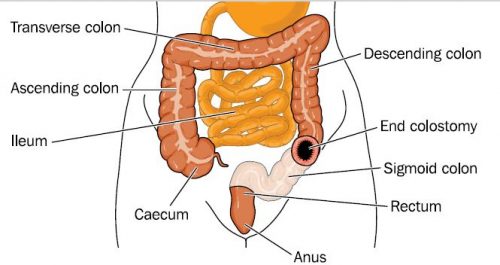

- Colostomy for rectal cancer. Less often, a person with rectal cancer may need to have a colostomy. This is a surgical opening, or stoma, through which the colon is connected to the abdominal surface to provide a pathway for waste to exit the body; such waste is collected in a pouch worn by the patient. Sometimes, the colostomy is only temporary to allow the rectum to heal, but it may be permanent. With modern surgical techniques and the use of radiation therapy and chemotherapy before surgery when needed, most people who receive treatment for rectal cancer do not need a permanent colostomy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by stopping the cancer cells’ ability to grow and divide. Systemic chemotherapy gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Common ways to give chemotherapy include an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle or in a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally).

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or combinations of different drugs at the same time.

Chemotherapy may be given after surgery to eliminate any remaining cancer cells. For some people with rectal cancer, the doctor will give chemotherapy and radiation therapy before surgery to reduce the size of a rectal tumour and reduce the chance of the cancer returning.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to destroy cancer cells.

For rectal cancer, radiation therapy may be used before surgery, called neoadjuvant therapy, to shrink the tumour so that it is easier to remove. It may also be used after surgery to destroy any remaining cancer cells

Vi

Vi