By Jonathan Corum and Carl Zimmer

Updated May 7, 2021

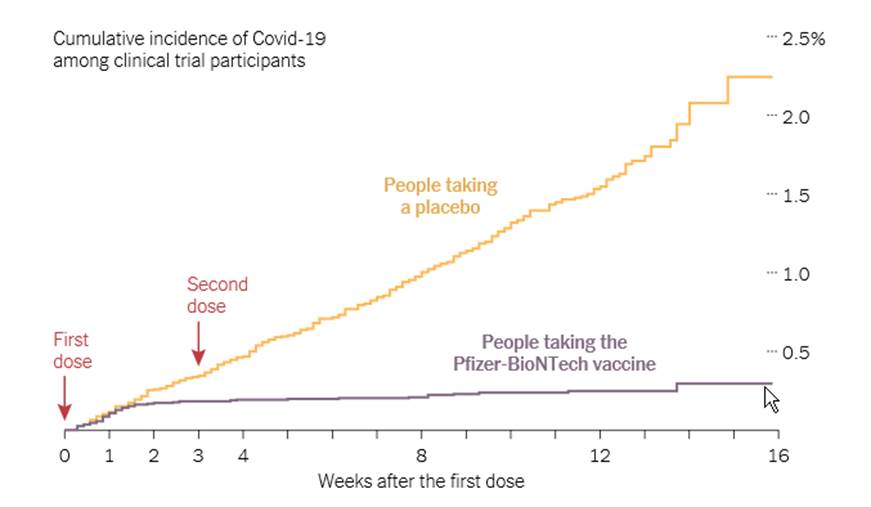

The German company BioNTech partnered with Pfizer to develop and test a coronavirus vaccine known as BNT162b2, the generic name tozinameran or the brand name Comirnaty. A clinical trial demonstrated that the vaccine has an efficacy rate of over 90 percent in preventing Covid-19.

Producing a batch of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine currently takes 60 days.

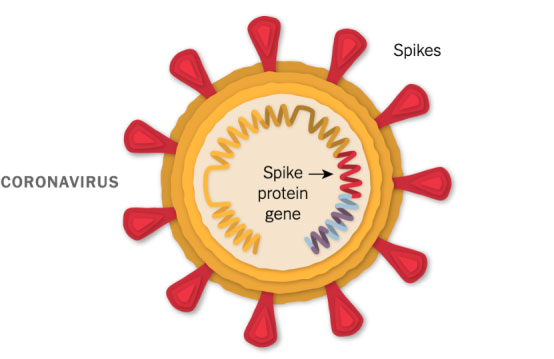

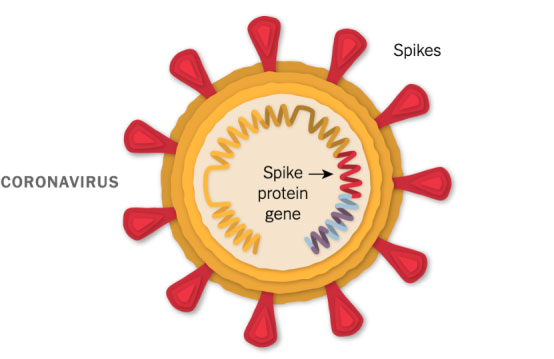

A Piece of the Coronavirus

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is studded with proteins that it uses to enter human cells. These so-called spike proteins make a tempting target for potential vaccines and treatments.

Like the Moderna vaccine, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is based on the virus’s genetic instructions for building the spike protein.

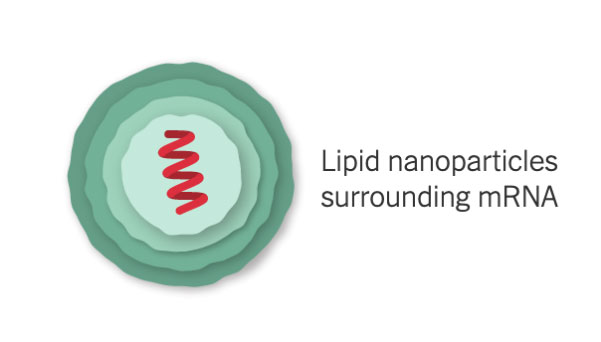

mRNA Inside an Oily Shell

The vaccine uses messenger RNA, genetic material that our cells read to make proteins. The molecule — called mRNA for short — is fragile and would be chopped to pieces by our natural enzymes if it were injected directly into the body. To protect their vaccine, Pfizer and BioNTech wrap the mRNA in oily bubbles made of lipid nanoparticles.

Because of their fragility, the mRNA molecules will quickly fall apart at room temperature. Pfizer is building special containers with dry ice, thermal sensors and GPS trackers to ensure the vaccines can be transported at –94°F (–70°C) to stay viable.

Entering a Cell

After injection, the vaccine particles bump into cells and fuse to them, releasing mRNA. The cell’s molecules read in the ribosomes its sequence and build spike proteins. The mRNA from the vaccine is eventually destroyed by the cell, leaving no permanent trace.

Some of the spike proteins form spikes that migrate to the surface of the cell and stick out their tips. The vaccinated cells also break up some of the proteins into fragments, which they present on their surface. These protruding spikes and spike protein fragments can then be recognized by the immune system.

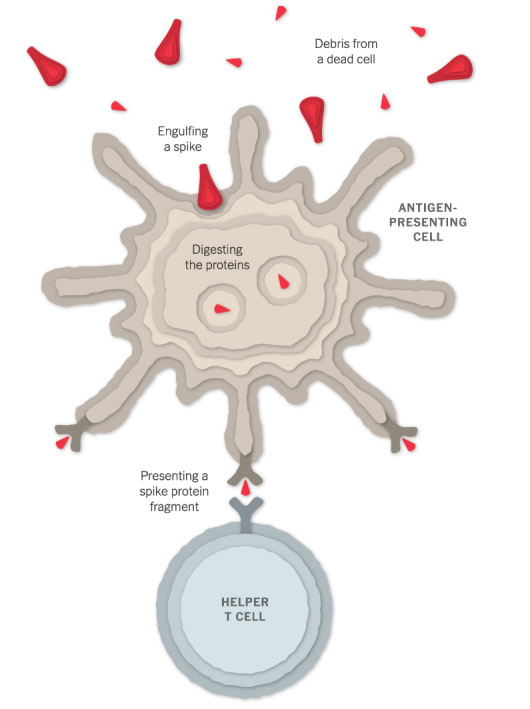

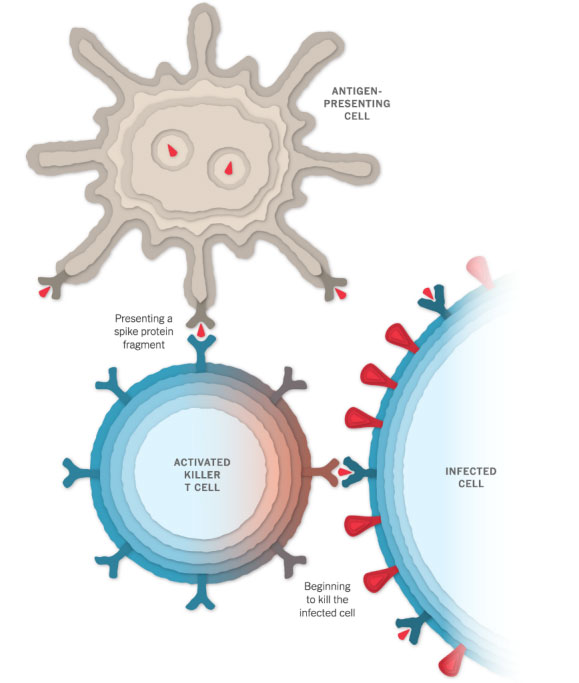

Spotting the Intruder

When a vaccinated cell dies, the debris will contain many spike proteins and protein fragments, which can then be taken up by a type of immune cell called an antigen-presenting cell.

The cell presents fragments of the spike protein on its surface. When other cells called helper T cells detect these fragments, the helper T cells can raise the alarm and help marshal other immune cells to fight the infection.

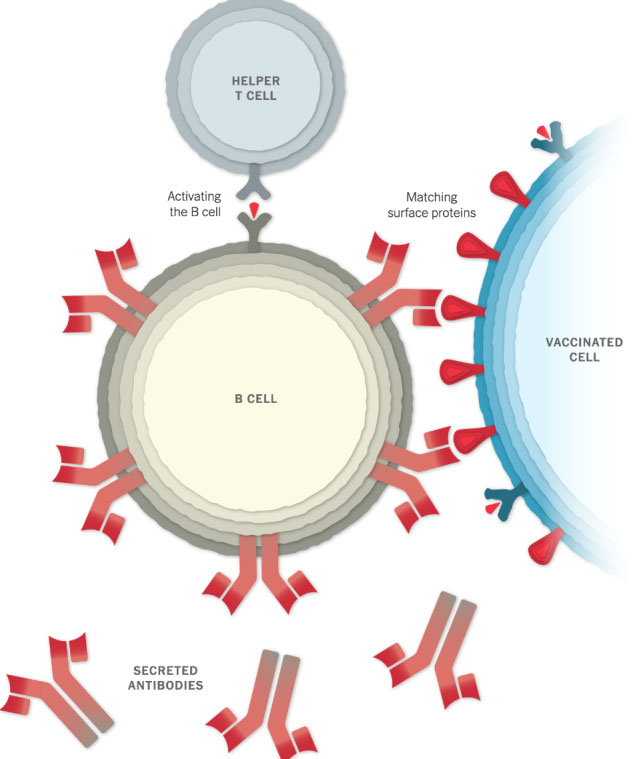

Making Antibodies

Other immune cells, called B cells, may bump into the coronavirus spikes on the surface of vaccinated cells, or free-floating spike protein fragments. A few of the B cells may be able to lock onto the spike proteins. If these B cells are then activated by helper T cells, they will start to proliferate and pour out antibodies that target the spike protein.

Stopping the Virus

The antibodies can latch onto coronavirus spikes, mark the virus for destruction and prevent infection by blocking the spikes from attaching to other cells.

Killing Infected Cells

The antigen-presenting cells can also activate another type of immune cell called a killer T cell to seek out and destroy any coronavirus-infected cells that display the spike protein fragments on their surfaces.

Remembering the Virus

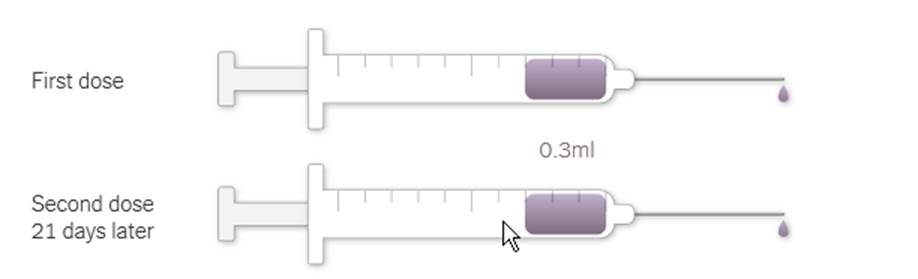

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires two injections, given 21 days apart, to prime the immune system well enough to fight off the coronavirus. But because the vaccine is so new, researchers don’t know how long its protection might last.

A preliminary study found that the vaccine seems to offer strong protection about 10 days after the first dose, compared with people taking a placebo:

It’s possible that in the months after vaccination, the number of antibodies and killer T cells will drop. But the immune system also contains special cells called memory B cells and memory T cells that might retain information about the coronavirus for years or even decades.

Preparation and Injection

Each vial of the vaccine contains 5 doses of 0.3 milliliters. The vaccine must be thawed before injection and diluted with saline. After dilution the vial must be used within six hours.

Vaccine Timeline

January, 2020 BioNTech begins work on a vaccine after Dr. Ugur Sahin, one of the company’s founders, becomes convinced that the coronavirus will spread from China into a pandemic.

March BioNTech and Pfizer agree to collaborate.

May The companies launch a Phase 1/2 trial on two versions of a mRNA vaccine. One version, known as BNT162b2, had fewer side effects.

July 22 The Trump administration awards a $1.9 billion contract for 100 million doses to be delivered by December, with an option to acquire 500 million more doses, if the vaccine is authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

July 27 The companies launch a Phase 2/3 trial with 30,000 volunteers in the United States and other countries, including Argentina, Brazil and Germany.

Sept. 12 Pfizer and BioNTech announce they will seek to expand their U.S. trial to 44,000 participants.

Nov. 9 Preliminary data indicates the Pfizer vaccine is over 90 percent effective, with no serious side effects. The final data from the trial shows the efficacy rate is 95 percent.

Nov. 20 Pfizer requests an emergency use authorization from the F.D.A.

Dec. 2 Britain gives emergency authorization to Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine, becoming the first Western country to give such an approval to a coronavirus vaccine.

Dec. 8 William Shakespeare, age 81, is among the first people to receive a shot of the vaccine in Britain, on the first day of vaccinations for at-risk health care workers and people over 80.

Dec. 9 Canada authorizes the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Dec. 10 Saudi Arabia approves the vaccine.

Dec. 11 The F.D.A. grants Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine the first emergency use authorization for a coronavirus vaccine in the United States. Mexico also approves the vaccine for emergency use.

Dec. 14 Vaccination begins in the United States.

Dec. 21The European Union authorizes the vaccine.

Dec. 31 Pfizer expects to produce up to 50 million doses by the end of the year, and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Each vaccinated person will require two doses.

January, 2021 Scientists grow concerned about the emergence of fast-spreading variants that might be able to evade antibodies. Tests on a variant called P.1, first identified in Brazil, show that Comirnaty will likely work against it as well. However, researchers find that antibodies produced by Comirnaty are somewhat less effective against another variant called B.1.351, first identified in South Africa.

Feb. 15 Pfizer and BioNTech register a trial specifically for pregnant women.

Feb. 26 The companies announce a study to develop a B.1.351-specific booster.

April 16 Pfizer says their vaccine may require a third dose within a year of the initial inoculation, followed by annual vaccinations.

April 20 Some vaccinated people are professing loyalty to the brand they happened to have received.

April 25 Nearly 8 percent of Americans who got initial Pfizer or Moderna shots have missed their second doses.

April 28 Pfizer has delivered more than 150 million doses of the vaccine to the United States, and expects to double that number by mid-July.

May 7 Pfizer and BioNTech apply for full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Sources: National Center for Biotechnology Information; Nature; Florian Krammer, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Vi

Vi