A fracture, or break, in the upper part of the shinbone (tibia) may result from a low-energy injury, such as a fall from a height, or from a high-energy injury, such as a motor vehicle accident. Proper identification and management of these injuries will help to restore limb function (strength, motion, and stability) and lessen the risk of arthritis.

The soft tissues (skin, muscle, nerves, blood vessels, and ligaments) also may be injured at the time of the fracture. Because of this, the orthopaedic surgeon will also look for any signs of soft-tissue damage and include this in plans for managing the fracture.

Whether the injury is treated with surgery or without, both the bony injury (fracture) and any soft-tissue injuries must be treated together.

CAUSE

Fractures that involve the upper fourth of the lower leg, or tibia, may or may not involve the knee joint. Fractures that enter the knee joint may render the joint imperfect and the joint surface irregular. Additionally, these fractures may result in improper limb alignment. Either of these factors may contribute to excessive joint wear (arthritis), instability, and loss of motion.

A fracture of the upper tibia can occur from stress (minor breaks from unusual excessive activity) or from already compromised bone (as in cancer or infection). Most, however, are the result of trauma (injury).

Young people experience these fractures often as a result of a high-energy injury, such as a fall from considerable height, sports-related trauma, and motor vehicle accidents. Older persons with poorer quality bone often require only low-energy injury (fall from a standing position) to create these fractures.

Many older persons may also have medical concerns, such as heart or lung problems, diabetes, or other diseases which must be considered and addressed.

Where a fracture is located within the knee and how much it is displaced (“moved”) is referred to as its “pattern.” The pattern of a fracture is determined by the force of the injury, in addition to how and where that force is applied to the limb. Forces can come from direct impact (dashboard); vertical impact (fall); bending (falls, sports and vehicular injuries); or some combination of such forces.

SYMPTOMS

A fracture of the upper tibia (shin bone) may result in injury to both the bone and the soft tissues of the knee region. Symptoms can be:

- Pain on bearing weight: typically, the injured individual is most aware of a painful inability to put weight on the affected extremity.

- Tenseness around the knee and limited bending: the knee may feel and appear tense, owing to bleeding within the joint. This also limits motion (bending) of the joint.

- Deformity around the knee: the leg may or may not appear deformed.

- Pale, cool foot: a pale appearance or cool feeling of the foot may suggest that the blood supply is in some way impaired.

- Numbness around the foot: numbness, or “pins and needles,” within the region of the foot raises concern about nerve injury or excessive swelling within the leg.

If these symptoms are present, you should have an assessment done in the emergency room.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of an upper tibia fracture of the knee joint is based both on clinical examination and imaging studies.

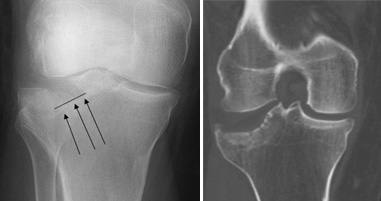

Multiple X-rays are obtained to identify the location within the knee and the severity of the injury. Frequently, a computed tomography (CT) scan is obtained as well.

Special procedures to assess blood supply are only occasionally required. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is of limited importance during the early stages of evaluation and treatment.

Doctors often use both X-rays (left) and CT scans (right) to determine the location and displacement of individual fracture fragments.

TREATMENT

Considerations

When determining whether to treat the injury surgically or non-surgically, the patient’s expectations, lifestyle, and medical condition are all considered. There are benefits and risks associated with both forms of treatment.

The decision to treat the patient surgically is a combined judgment made by the patient, the family, and the doctor. The preferred treatment is accordingly based on the specific details of the injury and the general needs of the patient.

In an active individual, restoring the joint through surgery is often appropriate because this will maximize the joint’s stability and motion, and minimize the risk of arthritis.

In other individuals, however, surgery may be of limited benefit. Medical concerns or pre-existing limb problems might make it unlikely that the individual will benefit from surgery. In such cases, surgical treatment may only expose these individuals to its risks (anesthesia and infection, for example).

Non-surgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment may include restrictions on motion and weight-bearing, in addition to the application of external devices (braces or casts). Typically, the soft tissues are assessed and X-rays are taken at prescribed intervals. Knee motion and weight-bearing begin as the injury and method of treatment allow.

Surgical Treatment

If surgical treatment is elected to obtain and maintain alignment, several devices may be considered.

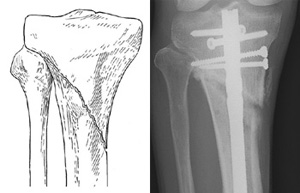

On the left, the upper quarter of the tibia is fractured (broken) but it does not enter the knee joint. Those fractures which do not extend into the knee joint may be treated with either a rod (shown right) or plate. A rod is placed within the hollow cavity of the bone.

Reproduced with permission from Bono CM, Levine, RG, Rao JP, Behrens FF: Nonarticular Proximal Tibia Fractures: Treatment Options and Decision Making. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001; 9:176-186.

Rods and Plates

In cases in which the upper one fourth of the tibia is broken, but the joint is intact, a rod or plate may be used to stabilize the fracture. A rod is placed in the hollow medullary cavity in the center of the bone, whereas a plate is placed on the external surface of the bone.

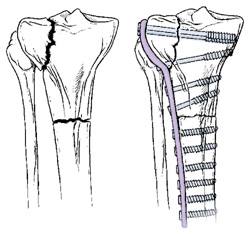

Plates are commonly used for fractures that enter the joint. If the fracture enters the joint and depresses the bone, lifting the bone fragments may be required to restore joint function. Lifting these fragments, however, creates a defect, or hole, in the cancellous (“crunchy”) bone of the region. This defect must be filled with material to keep the joint from collapsing. This material can be a bone graft from the patient or from a bone bank. Synthetic or naturally occurring products which stimulate bone healing can also be used.

To further stabilize this area, a plate with screws is applied.

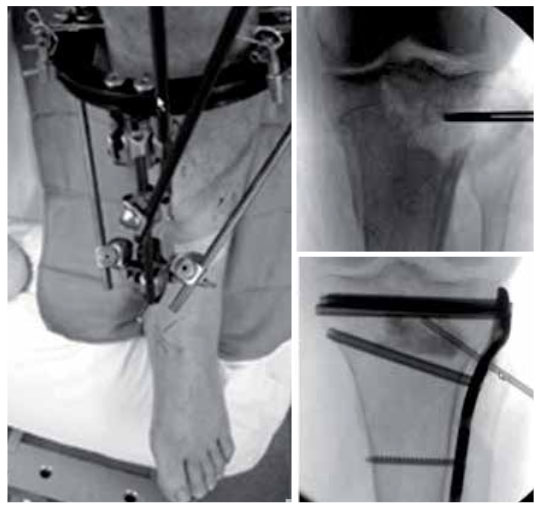

External Fixators

In some cases, the condition of the soft tissue is so poor that the use of a plate or rod might threaten it further. An external fixator may then be considered as final treatment. The external fixator is removed when the injury has healed.

Fractures that are depressed (shown left) must be elevated back up to restore the joint. This reduces the risk of arthritis and instability. When the depressed joint pieces are lifted a defect often remains below (shown right). This can be filled with various types of bone graft, synthetic or naturally occurring materials.

LIVING WITH THIS INJURY

The recovery phase begins shortly after nonsurgical or surgical treatment. During this phase, the patient must follow the orthopaedic surgeon’s recommendations. It is particularly important that the patient clearly understands the surgeon’s instructions about weight-bearing, knee motion, and the use of external devices (casts and braces).

Because proximal tibial fractures often involve a weight-bearing joint in an active individual, there are some long-term concerns. These include loss of knee motion and stability as well as long-term arthritis.

Your doctor will discuss your own personal concerns, and risks, and reasonable expectations. He or she will also discuss the impact these may have on activities of daily living, work, family responsibilities, and recreational realities.

REFERENCE: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS)

Vi

Vi