Retinal detachment is an emergency situation in which a thin layer of tissue (the retina) at the back of the eye pulls away from its normal position.

The retina is the part of your eye that sends visual signals to the brain along the optic nerve. This allows you to see. Retinal detachment separates the retinal cells from the layer of blood vessels that provides oxygen and nourishment. The longer retinal detachment goes untreated, the greater your risk of permanent vision loss in the affected eye.

Warning signs of retinal detachment include the sudden appearance of floaters and flashes and reduced vision. Contacting an eye specialist (ophthalmologist) right away can help save your vision.

SYMPTOMS

Retinal detachment itself is painless. But warning signs almost always appear before it occurs or has advanced, such as:

- The sudden appearance of many floaters — tiny specks that seem to drift through your field of vision;

- Flashes of light in one or both eyes;

- Blurred vision;

- Gradually reduced side (peripheral) vision;

- A curtain-like shadow over your visual field.

A few detachments may occur suddenly and the patient will experience a total loss of vision in one eye. Similar rapid loss of vision may also be caused by bleeding into the vitreous which may happened when the retina is torn.

CAUSES

Retinal detachment can occur as a result of:

- A sagging vitreous which is the gel-like material that fills the inside of your eye;

- Injury;

- Advanced diabetes.

How retinal detachment occurs

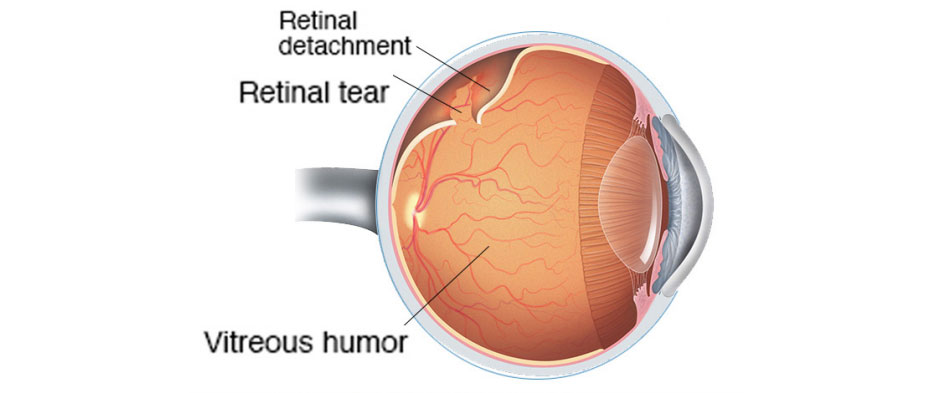

Retinal detachment can occur when the gel-like material (vitreous) leaks through a retinal hole or tear and collects underneath the retina.

Aging or retinal disorders can cause the retina to thin. Retinal detachment due to a tear in the retina typically develops when the vitreous collapses and tugs on the retina with enough force to create a tear.

Fluid inside the vitreous then finds its way through the tear and collects under the retina, peeling it away from the underlying tissues. These tissues contain a layer of blood vessels called the choroid. The areas where the retina is detached lose this blood supply and stop working, so you lose vision.

Aging-related retinal tears that lead to retinal detachment

As you age, your vitreous may change in consistency and shrink or become more liquid. Eventually, the vitreous may separate from the surface of the retina — a common condition called Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD).

As the vitreous separates or peels off the retina, it may tug on the retina with enough force to create a retinal tear. Left untreated, fluid from the vitreous cavity can pass through the tear into the space behind the retina, causing the retina to become detached.

PVD can cause visual symptoms. You may see sudden new floaters or flashes of lights (photopsia). These may be visible even in daylight. The flashes may be more noticeable when your eyes are closed or you’re in a darkened room.

RISK FACTORS

The following factors increase your risk of retinal detachment:

- Aging — retinal detachment is more common in people over age 50;

- Previous retinal detachment in one eye;

- A family history of retinal detachment;

- Extreme nearsightedness (myopia);

- Previous eye surgery, such as cataract removal;

- Previous severe eye injury;

- Previous other eye disease or inflammation.

DIAGNOSIS

Your doctor may use the following tests, instruments and procedures to diagnose retinal detachment:

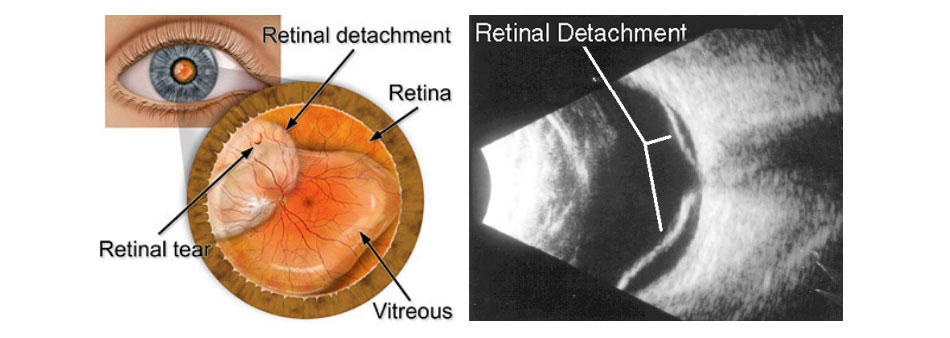

- Retinal examination: the doctor may use an instrument with a bright light and a special lens (ophthalmoscope) to examine the back of your eye, including the retina. The ophthalmoscope provides a highly detailed view, allowing the doctor to see any retinal holes, tears or detachments;

- Ultrasound imaging: your doctor may use this test if bleeding has occurred in the eye, making it difficult to see your retina.

Your doctor will likely examine both eyes even if you have symptoms in just one. If a tear is not identified at this visit, your doctor may ask you to return within a few weeks to confirm that your eye has not developed a delayed tear as a result of the same vitreous separation. Also, if you experience new symptoms, it’s important to return to your doctor right away.

TREATMENT

Surgery is almost always used to repair a retinal tear, hole or detachment. Various techniques are available. Ask your ophthalmologist about the risks and benefits of your treatment options. Together you can determine what procedure or combination of procedures is best for you.

Retinal tears

When a retinal tear or hole has not yet progressed to detachment, your eye surgeon may suggest one of the following procedures to prevent retinal detachment and preserve vision.

- Laser surgery (photocoagulation): the surgeon directs a laser beam into the eye through the pupil. The laser makes burns around the retinal tear, creating scarring that usually “welds” the retina to underlying tissue.

- Freezing (cryopexy): after giving you a local anaesthetic to numb your eye, the surgeon applies a freezing probe to the outer surface of the eye directly over the tear. The freezing causes a scar that helps secure the retina to the eye wall.

Both of these procedures are done on an outpatient basis. After your procedure, you’ll likely be advised to avoid activities that might jar the eyes — such as running — for a couple of weeks or so.

Retinal detachment

If your retina has detached, you’ll need surgery to repair it, preferably within days of a diagnosis. The type of surgery your eye surgeon recommends will depend on several factors, including how severe the detachment is.

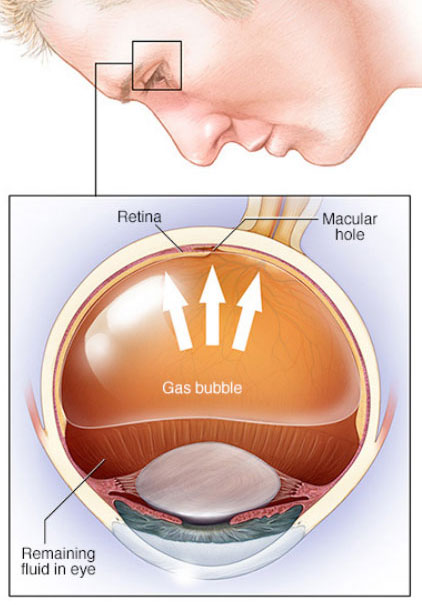

- Injecting air or gas into your eye: in this procedure, called Pneumatic Retinopexy, the surgeon injects a bubble of air or gas into the centre part of the eye (the vitreous cavity). If positioned properly, the bubble pushes the area of the retina containing the hole or holes against the wall of the eye, stopping flow of fluid into the space behind the retina. Your doctor also uses cryopexy during the procedure to repair the retinal break.

Fluid that had collected under the retina is absorbed by itself, and the retina can then adhere to the wall of your eye. You may need to hold your head in a certain position for up to several days to keep the bubble in the proper position. The bubble eventually will reabsorb on its own.

You cannot fly or drive while the gas bubble is present.

- Indenting the surface of your eye: this procedure, called scleral buckling, involves the surgeon sewing (suturing) a piece of silicone material to the white of your eye (sclera) over the affected area. This procedure indents the wall of the eye and relieves some of the force caused by the vitreous tugging on the retina.

If you have several tears or holes or an extensive detachment, your surgeon may create a scleral buckle that encircles your entire eye like a belt. The buckle is placed in a way that doesn’t block your vision, and it usually remains in place permanently.

- Draining and replacing the fluid in the eye: in this procedure, called vitrectomy, the surgeon removes the vitreous along with any tissue that is tugging on the retina. Air, gas or silicone oil is then injected into the vitreous space to help flatten the retina.

Eventually the air, gas or liquid will be absorbed, and the vitreous space will refill with body fluid. If silicone oil was used, it may be surgically removed months later.

Vitrectomy may be combined with a scleral buckling procedure.

Pneumatic Retinopexy

HOW SUCCESSFUL IS SURGERY?

Surgery is usually successful in reattaching the retina in 8 out of 10 patients first time round.

However you may need two or more operations to complete the treatment. Some people have good vision with a retinal detachment if the central part of the retina (macula) was still in place. After surgery the vision may be initially worse because of the surgery. You may need to change your glasses once the eye has healed to get best vision to improve and may not return fully to normal.

WILL MY VISION GET BACK TO NORMAL?

It will depend on the extent and duration of retinal detachment. After surgery your vision may take several months to improve. Peripheral vision tends to return to normal after successful retinal detachment surgery. Reading vision is more likely to recover if the central part of the retina (macula) was not involved (macula on retinal detachment). The outcome tends to be worse if your macula was detached.

The longer the macula is detached prior to surgery the less visual improvement can be expected after surgery. Therefore it is important to have a retinal detachment treated as soon as possible, before the macula detaches.

Vi

Vi